The “sport” resembled a game of dodge ball in which he and other Americans assigned to Battery A, 2nd battalion of the French Artillery, tried to dodge artillery shells fired at them by Kaiser Wilhelm’s German army.

In case my grandfather might not have found the game sporting enough, fate assigned him the task of dodging those shells while driving a wagon filled with artillery shells the French would soon throw at the German “dodge ball” team.

Had my grandfather been an easier mark that day, my father’s birth, mine, and all other related would never have appeared on our family tree, adding to the casualties of a war that I recently was reminded had an already obscene amount.

The Godmother

I revisited the diary and war recently because Flossie Hulsizer made me an offer I couldn’t refuse: a few slices of her strawberry-rhubarb pie in exchange for a 45-minute talk to the affable members of the Clark County Genealogical.

After accepting her offer, finding the diary and grabbing a squeegee to wipe the “pie drool” off my laptop screen, my fingers soon discovered how much easier it is to make my way into the past with the new AI-enhanced search engines.

Even with my self-inflicted typos, clues in my grandfather’s diary led me to maps that helped me follow his trail through the Meuse-Argonne offensive, which, I learned, began two days before his 22nd birthday, which he celebrated Sept. 26, 1918.

Even during the government shutdown, National Archives website told me the battle I’d not heard of was the deadliest in our nation’s military history. Of the million men of the American Expeditionary force fighting engaged in it, 26,000 were killed and 96,000 wounded or injured.

That’s roughly half the number of Americans killed in the entire Vietnam War in a mere 48 days with (according to the Archives) this sobering if unsurprising result: The number of graves in the American military cemetery at Romagne is far larger than those in the more commonly known (World war II) site at Omaha Beach in Normandy.

(For those interested, the National Archives has scads of videos with World War I footage for the searching.)

No sequel, please

Because I’d watched the Netflix series “Peaky Blinders,” my fingers also sought out casualty figures from Battle of the Somme, where the fictional Tommy Shelby was said to have fought. There, I discovered 57,000 British soldiers were killed or wounded in a single day of a battle that had casualty count (killed and injured) of — read it and imagine the weeping it caused — 490,000.

As online Britannica tell us: “The casualties suffered by the participants in World War I dwarfed those of previous wars: some 8,500,000 soldiers died as a result of wounds and/or disease.”

That scale of death and suffering helped me to understand something that had seemed almost laughably incomprehensible: How members of a species with a history for repeatedly killing one another in wars from the dawn of time might foolishly believe that theirs it might be what they called World War 1: The war to end all wars.

But who, having witnessed the hell that had ground on from 1914-1918, could have stomached the idea that it would have a sequel?

The same Britannica entry tells us, “The greatest number of casualties and wounds were inflicted by artillery,” my grandfather’s wartime trade. It was so central to what was called “mechanized warfare” that the term “shell shock” was coined to describe the psychological havoc it had on so many of its veterans.

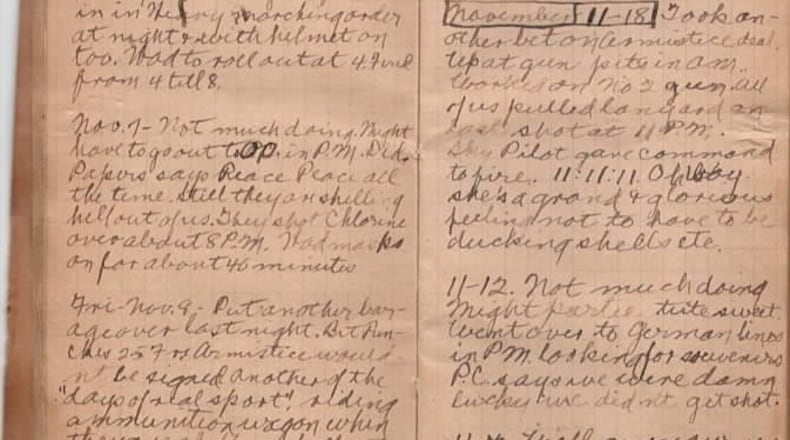

Two days before his “day of sport” entry, my grandfather testified to it.

“Shelling us to beat hell & then some today. Tore up No. 4 gun pit. I’ll admit that I was in Hell & that I am shaky … Some of these birds are worse than that."

A P.S. from history

Two Mondays before war’s end — and with Pvt. Stafford unaware of the hell that was to come — his diary entry opens on a happy note with the words “Found a billet today.”

For a soldier used to tent life, a billet (usually a civilian’s home), was something of a luxury.

My grandfather’s remark “some class, I’ll say” indicates the true luxury of his billet, the one-time headquarters of not just German general, but a celebrity among German generals. As a Washington, D.C. Museum I’ll name in a moment tells us, “Erich Ludendorff … gained renown during the First World War (when) he and future German President Paul von Hindenburg built a military empire in the east that lasted until the Germany’s defeat in 1918.”

There follows evidence that my grandfather stayed that night in a place once occupied by a man instrumental in helping to create World War I’s sequel. “Ludendorff was deeply antisemitic, an early supporter of Hitler, and … was pivotal in the creation and diffusion of the fictitious ‘Stab-in-the-Back’ myth, which blamed Jews, liberals, communists, democrats, and war profiteers for the defeat of Germany in World War I.”

That reminder of the dangers of such fictions is brought to us by the Holocaust Museum.

A family P.S.

This deeper dive into world and family history gave me an excuse to make a rare phone call to Florida to talk with my Uncle Mike Stafford, the last born and last surviving of Mark and Agnes Bral Stafford’s five children.

Happy to live several floors up in a beachfront condo with a beautiful view of the Atlantic, he said that, aside from a diary, the attic of the Stafford house held three of his father’s wartime keepsakes: “A helmet, a rifle and his gas mask.”

From a memory he confesses isn’t what it used to be, he recalls just one war story his father told him: “When they put him in the hospital (following a gas attack), he said they put the people that were going to die in one end of the tent, and the people who were going to survive in another.”

He then added that when he lost him at age 16, “I hardly knew my father.”

The obituary in the Feb. 29, 1956, edition of Marquette’s Mining Journal tells us that he worked from 1920 until his death at 59 as a brakeman and conductor for the Duluth South Shore & Atlantic Railway; was a member of St. Michael’s Church, the Holy Name Society, the American Legion and the Knights of Columbus; and was president of the Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen.

Now 86, my Uncle Mike remembers just two experiences with his father: a childhood ride in caboose from St. Ignace, Mich., to Marquette, in which the caboose may be the most memorable element; and time spent with him St. Mary’s Hospital in Marquette during the two-and-a-half months his father was dying of cirrhosis of the liver caused by alcoholism.

“I’ve often wondered,” Uncle Mike told me, “if it was (caused by) something that happened in the war.”

Perhaps on one or more of his “days of sport.”

About the Author